The Bucs' offense and what it means to 'layer' an offense

How Bruce Arians, Byron Leftwich and Tom Brady tie their run-game to play-action and RPOs.

One of the most important building blocks for any modern offense is the idea of ‘layering’ one concept on top of the other.

Layering is as it sounds: Adding fresh dimensions to an idea, a formation, a motion, a movement, a whatever, that builds on top of the base construct. Layering is often used as a synonym for pay-off plays. A coach carefully, artfully, builds in a tendency, before self-breaking that tendency for a big, explosive, pay-off play. Jet-give. Jet-give. Jet-give. Jet-give. Reverse!

Lane Kiffin is the master at building towards pay-off plays. But there are other more subtle ways a coaching staff layers their offense. For most coaches, adding layers is simply about not tipping what’s about come: About breaking a tendency before it can truly gather steam and a defense can get a read on what’s coming through formation or specific alignments.

No one – not anywhere – does a better job of layering concepts than Bruce Arians, Byron Leftwich, Tom Brady, and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

At root, layering is about keeping the defense off balance. About asking linebackers to shuffle their feet, rather than triggering and firing one way or the other. About having the safeties creep down or shuffle back, not knowing if their eyes are lying to them one way or the other.

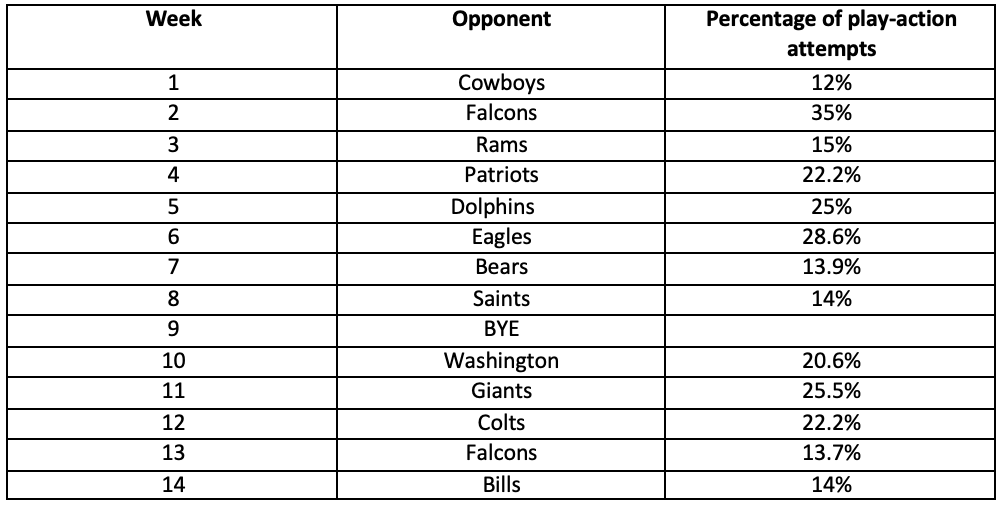

Arians, Leftwich and company remain among the best (and we’re splitting hairs between Tampa and Green Bay) at tying their run-game to their play-action game – and building in RPOs off those same structures. Tying the two together – having the action look, feel, sound like a run play at each and every junction – can keep the defense off balance. The Bucs run play-action on only 20-odd percent of dropbacks. And that figure has dropped throughout the season — they’re dead stinking last in play-action rate since their bye.

But the threat that Brady might pull the ball and try to target one of his innumerable weapons down the field is enough to force linebackers to check themselves. And adding any kind of beat to the linebacker’s fit is one way a coach can help boost his run-game.

Coming out of the bye, Tampa has made a bunch of nifty adjustments (some of which I will explore in more detail over the coming weeks – there is a lot to sift through). But one thing has really jumped out: The shift to a more gun-laden, spread-to-run running game.

Throughout the Arians-Brady partnership, the run-game has served as a cheat code. It allows the team to run defenses out of staunch two-high safety looks (and if you spin against Tampa, you’re in big, big trouble) or it can rest there as an every-down thumper, constantly churning out yards, constantly moving the ball.

Add to that, throughout the Arians-Brady partnership the Bucs’ offense has been able to live in two worlds: A spread-out passing game; a bigger-bodied thumping game. The Bucs are the pinnacle of the moniker ‘run two systems from the same personnel grouping’. If you can hit that in the modern NFL, that’s where football nirvana lies.

It’s a world that comes naturally to Tampa. Why? In short: Rob Gronkowski.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.