There is more to come from Kyler Murray

For eight weeks last season, Kyler Murray was as good as any quarterback in the NFL -- then things cratered. On the hows, the whys, and what comes next.

For eight weeks last season, Kyler Murray was less a professional quarterback and more a footballing supernova.

Sometimes you can just tell a player has made a mini leap. You can see it. You can feel it. Over that stretch of the season, Murray vaulted from a fun-to-watch, he’ll-put-it-together-someday quarterback into the league’s upper tier.

Then something switched. Murray got hurt. He missed time. The Cardinals changed up their offense – from a spread-out, receiver-based concoction into a more balanced, condensed, get-a-tight-end-on-the-field set-up. As has become custom throughout his career, Kliff Kingsbury’s offense flatlined – to almost memeable proportions.

There is a whole stack of reasons and theories: The Cardinals offense becoming too predictable (Kingsbury, oddly, taking stuff away during the season rather than adding more in); injuries; wear and tear on Murray, making him a lesser off-script threat; an offensive line that could not keep up as the season went along. All are true to some degree.

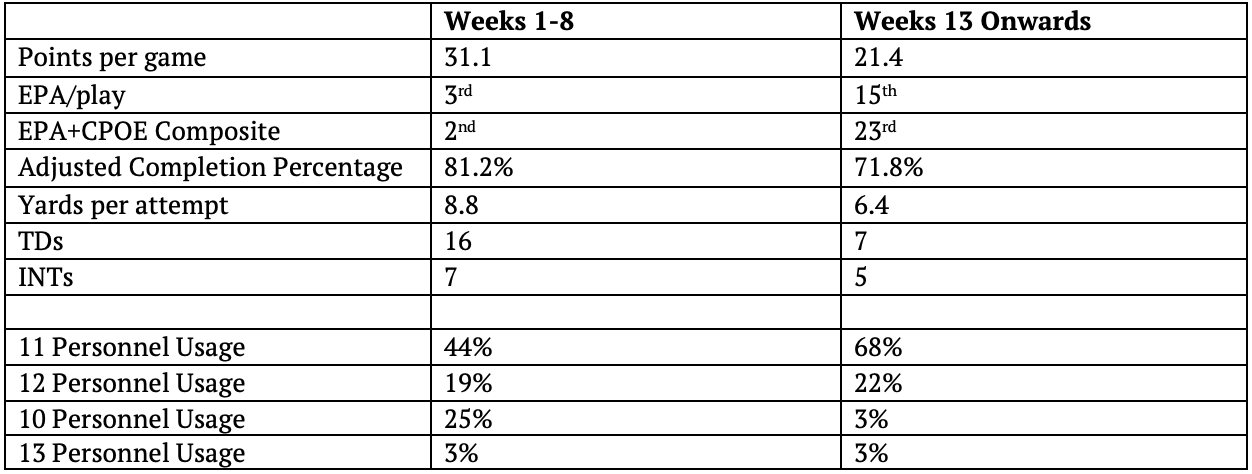

Whatever the specifics, the numbers are jarring:

As the Cards changed the profile of their offense, the whole machine fell apart. Kingsbury shifted to tighter and heavier sets, ditching a league-high 10 percent of ten personnel usage (1 back, 0 tight ends) and instead banking on Zach Ertz to be the midseason difference-maker – who the Cardinals acquired from the Eagles prior to the trade deadline.

It was a dud. Things were slower and more ponderous. As the offensive line nose-dived, Kingsbury and co. banked on more vertical concepts, an odd contradiction.

Murray’s play tanked, too. He missed basic throws. The same electricity that defined the early portion of the season was there, but he started to miss the basic layups, relying too much on the out-of-structure sorcery that had served as the cherry on top rather than the base of the offense early in the year. Over the final seven games – regular season and postseason, after he returned from injury – Murray ranked 23rd in the EPA+CPOE composite, which measures the value of a play and how much the quarterback can be deemed responsible for the value. Murray fell from the ranks of the elite (3rd in the league) to the class of not-very-good, sitting behind the likes of Jared Goff, Drew Lock, and something called Tim Boyle, which sounds like a Victorian-era medical practice.

Murray was and is far from the problem. Heading into next season, he’s the only certainty in Arizona: the offensive line is shaky; the skill positions leave a lot to be desired; the defensive front is weakened, having a compound effect on what is needed and what will be expected at the second level and in the secondary. Murray, in many ways, is just that little bit too good to cost coach Kill Kingsbury and GM Steve Keim their jobs — he is almost singularly responsible for the pair receiving bumper four-year contracts.

But that’s not to say Murray cannot improve, which is both nitpicking and terrifying— at least for those trying to slow the quarterback down.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Read Optional to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.